Inclusion Category

Everyone Welcome

by Gill Simmons

B+B R+D has commissioned this article as part of our ‘test’ and ‘reflect’ inclusion action research. All of the articles in this series represent the views of the author and not of B+B R+D or our partner organisations.

Some of the articles describe experiences of discrimination that readers may find upsetting.

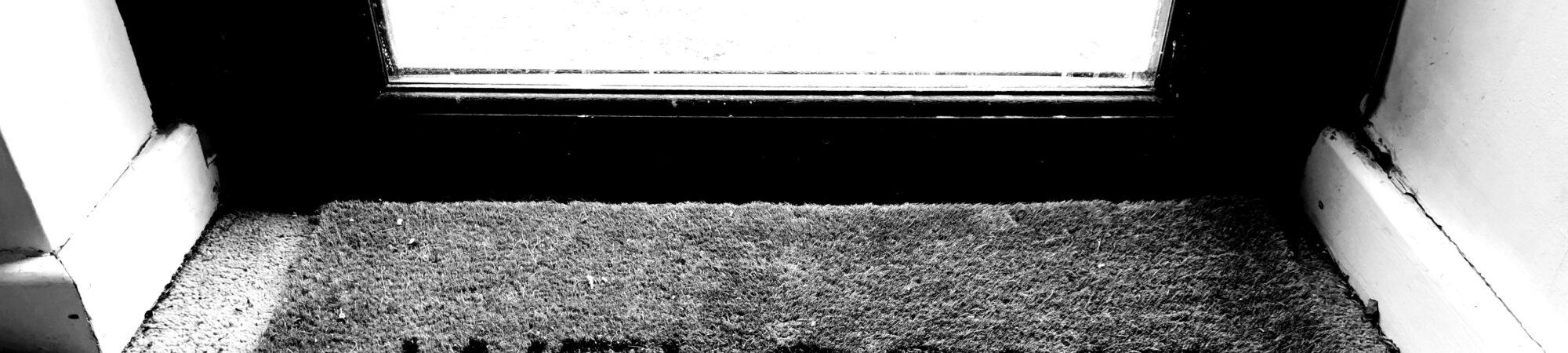

The mat by my door says WELCOME. The word faces into the house. I place it this way round to remind myself when I go out that I’m welcome in the world.

Feeling welcome isn’t a given for me. I often don’t feel like I fit in. Mostly I feel like I am swimming against the current, going against the grain or off the beaten track. This could be because I am a 45 year old, working class solo mother, precariously housed on the very edge of town who works freelance in the arts.

I don’t know many other people like me, who are walking the road I’m walking. I know it’s the right road for me, but on this road are stumbling blocks, potholes, razor-sharp turns and a seemingly perpetual blind summit.

That’s a lot of metaphors. Let’s get concrete. Since I began freelancing in 2013 (had to leave secondary drama teaching when I became a solo parent) I have mostly survived by applying for small, short-term community-focused grants to deliver community art projects in Hartcliffe and Withywood (and occasionally devising theatre with my colleague which we tour as best we can). I grew up in south Bristol in a working class family who had absolutely no idea how to support or encourage my interest in the arts, and who still actively attempt to get me to stop all this hippy nonsense and find a proper job. There are many young people in a similar situation in Hartcliffe and Withywood today. So essentially, I’m trying to be for others the person I could have done with myself 35 years ago. I know this to be essential work if the status quo is ever to shift and shift it must. Therefore I will not get off this road, however hard the going gets.

Small short-term community focused grants aren’t enough to live on. My working class family can’t subsidise me. I don’t have a partner but I do have 3 dependents. So of course I have to look for other opportunities.

Other people’s opportunities can be grand. But they can also be the stumbling blocks, potholes and razor-sharp turns on my road. I’m fairly convinced this is because often other people’s opportunities are not written by people like me, because other people’s opportunities make a LOT of assumptions.

The rest of this will be me detailing these assumptions, explaining how they affect me, and some recommendations for how organisations that create arts opportunities, can remove the stumbling blocks, fill in the potholes or straighten out the road a little for working class creatives (and doubtless many other kinds of folk along the way). So if that isn’t you, or if you don’t genuinely care about the democratisation of the arts, then I suggest you stop reading here.

DIGITAL ACCESS

Everything is advertised online, applications have to be made online, and interviews are often held online.

My landlord doesn’t think reliable WiFi is something they should provide, and they have specifically banned me from getting better WiFi put in. Sometimes I lose all connectivity. Sometimes it takes me 14 hours to upload a 4 minute video to YouTube. My poor internet connection means I’m regularly thrown out of zoom calls.

(Before you suggest that I move house, I have tried. Just know that if you’re a solo parent with no salary and no guarantor, estate agents won’t even let you view properties, let alone rent them. So I’m stuck making the best of what I have.)

Poor and unreliable connectivity means it can take me significantly longer than people with reliable WiFi to apply for things. It also means I can present as a chaotic nuisance in zooms, because I frequently glitch, freeze and suddenly vanish.

Recommendations:

Avoid short application periods. Get opportunities advertised as early as you possibly can.

Give people the option to be interviewed on the phone and don’t make it feel like a phone call is only ‘second-best’.

Remember not everyone has full control over their living environment.

AVAILABILITY

Some opportunities require an almost immediate start.

I just about cope by having the month I’m in, plus the next two, as packed with paid work as possible. And for me, a packed month means literally working most days. Community arts and touring family theatre shows do not carry significant cultural capital. This is totally wrong, of course, but it’s the case. No one wants to pay community artists much and no one wants to give original devised family theatre by a pair of random unknowns a decent run in a venue on a good fee. So I have to work most days of the month to bring in just about enough money.

Some freelancers operate by building a high status reputation for themselves and by operating occasionally within the corporate world who can afford to pay very high day rates. This approach of course requires your work to carry significant cultural capital and for the artist to have significant social capital. Artists who manage this can afford days off each month, as can those with supportive wealthy families or high-salaried partners. Those with lots of days off in the month have more scope to take roles with immediate starts. For this reason, if you post an opportunity with a fairly immediate start, you are very unlikely to get many if any working class artists apply.

Recommendations:

Plan ahead and advertise opportunities now that don’t need availability until at least 3 months ahead. More, ideally. This will of course sometimes be impossible. But if your opportunities are ALWAYS needing people to be available immediately (by which I mean with less than 3 months notice) then I urge you to address this.

These threads by Sofia Galluci and Rafia Hussain are worth a read if you’d like more perspectives on this.

RATES OF PAY

It’s a stone-cold fact that rates of pay for community art and family theatre performance work are often less than they should be. I think this because people setting rates don’t always remember (or genuinely believe) that creative freelancers are skilled specialists, don’t consider the number of hours the freelancer will actually be working, and don’t consider how physically heavy or mentally demanding the work actually is.

Recommendations:

When shaping an opportunity, pay artists to consult with you on how specialised the work is, how many hours the work is likely to demand, and how heavy the work will actually be. Let artists advise you on an appropriate fee and honour it. Do not just pull a lump sum out of the air that “feels right”. People like me have to take that, break it down and work out whether it’s worth our while even to apply. More often than not, it isn’t.

Think about your financial optics. If you’re one of several colleagues all on salaries, and your organisation’s accounts on Companies House are pretty beefy, at least understand why freelancers earning less than £10k a year who are on benefits might well feel it’s appropriate to ask you for at least a fair rate of pay.

Pay freelancers for meetings and admin as well as for actual project delivery.

Never tell someone they are “too expensive”.

Oh, and of course, be super transparent about the rate of pay and how it’s been calculated when you advertise opportunities. This should be an obvious one, but…

LOCATION

I live on the very edge of town. I live where I live because it’s near my parents. I’m an only child and they’re both well into their 80s. Also, it’s slightly cheaper because it’s not perceived as a “desirable area”.

The buses into town are massively unreliable (often they just don’t show up at all). It’s too far for me to walk to any buildings that house arts opportunities, which are predominantly in central locations. City centre parking is scarce and expensive. I could cycle, but that takes considerably longer than the bus or the car, which means more hours spent travelling that won’t be reimbursed. I know there are health benefits, but my situation means I have to prioritise earning money to support my dependents.

All this means it can feel like I’ve been asked to climb Kilimanjaro when I’m asked to be in a central location by a certain time. If I’m late because the bus didn’t show, I look unreliable and disorganised. If I have managed to find parking, I’m either out of pocket or need to have the brass neck to ask for the parking to be reimbursed. I do have that kind of brass neck, by the way, but not everyone does.

Recommendations:

Do you always need freelancers to come to you? Could you not offer to come closer to them at least sometimes? I have met a lot of arts people who admitted they’ve never been to Hartcliffe or Withywood. If you’re an organisation that’s genuinely interested in reaching people from the whole city, this practice could be super useful for you.

Make explicit that you can reimburse travel expenses if required.

Make getting reimbursed a simple and quick process.

CARING RESPONSIBILITIES

Another stumbling block are my caring responsibilities as a solo parent. There’s no one to delegate school runs to, and I’m vulnerable to any one of them (or my elderly parents) falling ill at any time. If anyone needs looking after, that’s always on me and only me. I’ve no siblings.

I was once contracted to deliver a project that called for ten workshops over several months plus other elements. I couldn’t deliver one workshop as one of my children fell suddenly ill. The project coordinator responded by docking the fixed fee and stating “the contract doesn’t give parental leave”. That still leaves a sour taste. It felt discriminatory, unnecessarily pedantic and inflexible.

A big part of this is because my extended working class family don’t think I should be doing this kind of work, so they don’t offer practical support because that would only encourage me. Some families still see women as default caregivers and expect them to be available at any given moment to look after someone else. This is a pothole I sometimes fall into. But from the perspective of some commissioners, I probably just look flaky, unreliable and disorganised, or someone who doesn’t have the right priorities.

Someone once tried to tell me when I’d had a logistical collapse that it was my fault because I hadn’t built up good enough support networks. Yeah, really.

Recommendations:

Build flexibility into opportunities for freelancers with caring responsibilities and make that flexibility explicit in the call out. Acknowledge openly that some people have far more variables in their lives that can directly impact their ability to access work, particularly if it’s work that’s time and/or space specific.

Remember that statistically, more caring work falls to women.

Find ways to make working parents feel genuinely welcome, however that looks for them.

If freelancers sometimes have to prioritise caring responsibilities over your project, try to find a way of ensuring they can still earn what you told them they’d earn.

Don’t punish people financially if they have to put their caring responsibilities first.

Don’t assume people have supportive personal networks, and never criticise them if they don’t.

NETWORK

I once watched a recorded zoom of a workshop for theatre artists and producers. It was about marketing theatre. Lots of practical suggestions were made, and then there was this moment where someone said “family and friends network” and everyone laughed knowingly.

Apart from my children, no one I’m related to has ever seen a show I’ve made. Of course, this also means they don’t encourage their friends to come to see my shows either. I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of times university or school friends I’ve managed to keep in touch with have been in the audience since I started making theatre in 2015. If there’s a hint of small violin here, I hope you’ll forgive me.

I am convinced that artists who thrive the most and therefore have the most confidence to apply for opportunities have at their foundation a reliable, supportive social network of people who believe they should be creating, and who are proud to be associated with their work. Of course, some working class artists have this, and some artists who aren’t working class don’t have this, but it is an unequivocal fact that “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know” still holds sway, and it's undeniable that this system is less likely to benefit working class artists as, on the whole, they will have inherited fewer contacts in the arts industry than more privileged people.

Recommendations:

When you hire a working class creative, could you adopt a policy in your organisation of actively sharing your social and cultural capital with working class artists who may not have much of their own network, in order to power their work forward? Show up for them, then actively, publicly and consistently recommend their work using your personal and your professional platforms.

If you only ever pay proper attention to artists that other organisations are talking about, you’re perpetuating a hermetically sealed loop that is less likely to include working class artists.

LANGUAGE

Most of my work has necessarily been supported by either community or non-arts funding. Necessarily because these grants as a rule have a simpler application process than arts-specific funding. Anyone who has ever tangled with Grantium will doubtless back me up on this one. Community and non-arts funders want matter-of-fact, specific, direct language. What will you do, who is it for, why does it matter, and how much does it cost?

I am therefore not used to discussing my work in rarefied, hifalutin terms. It doesn’t mean it isn’t complex, nuanced, and considered work because it is. But if you write a call out that reads a little like something from the artybollocks generator, despite having an MA in Drama and Theatre, I will struggle to recognise any correlation between what you’re looking for and my work, even though actually I could be just what you need.

As a side order, this thread by Sarah Meadows about working class communication styles and how it can cause problems when working within a predominantly middle class arts field is well worth a read.

Recommendations:

Be transparent. Definite your terms. Avoid jargon.

Don’t break your word. If things need to change, tell people straight away, be honest and apologise if you mess up.

Why remove these barriers?

I believe we need to remove systemic barriers and democratise who gets to work in and enjoy the arts. Otherwise people’s bodies, age, socio-economic status, postcode, caring responsibilities and other entirely arbitrary factors will limit them, only making them welcome in certain spaces and in certain kinds of work. And I don’t know about you, but that’s not the kind of world I want my children to grow up in.

Further links, some tightly, some slightly more loosely connected:

The Bottom Line: class in the workplace (Radio 4)

Should Class Snobbery Be Banned (New Statesman)

Running Culture: on broadening the field of cultural leadership (Stephen Welsh)

The Transformational Power of Art (Chris Sonnex)

If education is all about getting a job, the humanities are left just to the rich (Kenan Malik)